I was recently asked to choose and implement a CMS solution for a digital agency to manage multiple websites in a single installation. For a huge number of reasons, the prime candidate was https://wordpress.org/. It's free and open-source, has a huge user community, it's easy to use, and has a multisite feature. It's unquestionably a commercially-proven and mature product. But, I had my reservations.

Using WordPress in a conventional way means making an installation, creating a theme (or modifying an existing one) and accepting that every further customization will have to find its place in the ecosystem created by the CMS: the programming languages and technologies (PHP and MySQL) as well as the clever — but quite complex — world of plugins, themes, actions, filters and whatnot.

I've always envisioned content as the center of everything on a website. The nature and creative concept of each individual project should dictate what medium and technologies can best deliver the content, not the CMS.

I don't want to have my technology choice for a project limited to PHP just because WordPress is built on it, and I want developers to have the freedom to choose whatever technology stack they see fit to create independent and self-contained websites, not just WordPress plugins and themes.

¶ Creating a middleman

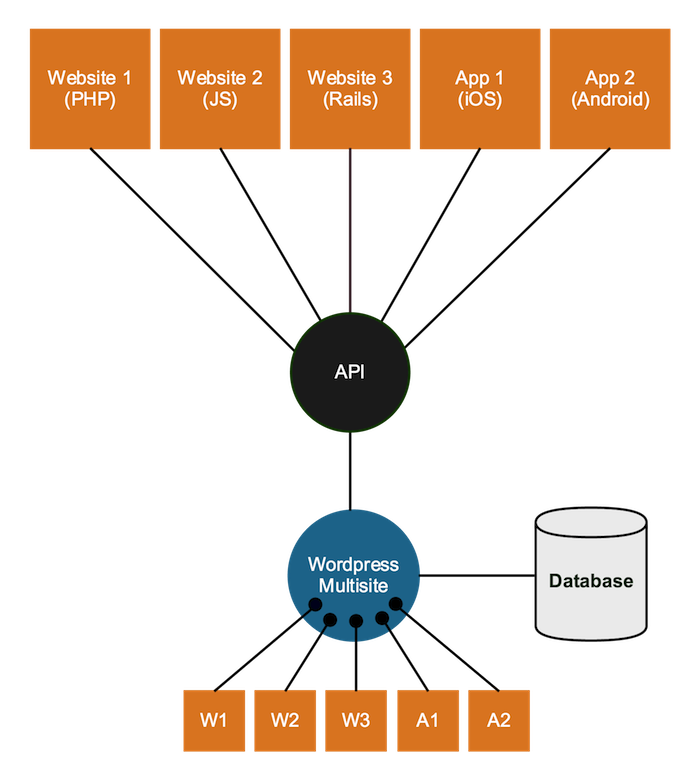

An API-first solution, with an intermediate layer that sits between the website and the CMS, can free WordPress from dealing with any frontend business and leave it with the sole purpose of managing and delivering content.

This "middleman" layer is capable of speaking a universal language (JSON is my preference) that different end platforms can understand and process in a way that suits the project.

I'm thinking something like this:

¶ Adapting WordPress

In the normal WordPress world, people would access the website through a human-friendly domain name, the content would be pulled from the database, and a theme would then format and display it in an HTML page. That page would also most likely have a visual interface for users to browse through posts and pages, and filter content based on categories, tags, or any other taxonomy.

Our API-first WordPress won't have any of that. The only input we'll accept from users will come in the URL of the requests they send, which we'll have to parse in order to extract the type of data we need to deliver, the format, and the filters to pass it through.

¶ Building a plugin

There are good ways and there are nasty ways of adding and changing functionalities in WordPress. In a nutshell, messing with the core codebase is bad news, you should create a plugin instead.

But how will our plugin work exactly? How can it change the default chain of events followed by the CMS to read a request, get things from the database, and send something back? That can be done with a hook — an action, more specifically — which allows us to throw a monkey wrench in the works and intercept the request, taking full control of what happens from that point on.

So let's start laying out the foundations for our plugin.

class API { public function __construct() { add_action('template_redirect', array($this, 'hijackRequests'), -100); } public function hijackRequests() { $entries = get_posts($_GET['filter']); $this->writeJsonResponse($entries); } protected function writeJsonResponse($message, $status = 200) { header('content-type: application/json; charset=utf-8', true, $status); echo(json_encode($message) . "\n"); exit; }}new API();It's a good practice to wrap the plugin in a class construct to avoid polluting the global namespace with loose functions, potentially leading to naming conflicts.

We then start by registering a function with the template_redirect action, which fires after the initialization routine takes place and right before WordPress decides which template to use to render the page.

Then we fire get_posts(), which accepts an array of filters as its argument and returns an array of matching entries (the function name can be misleading; it can return both posts and pages).

So after saving the file and activating the plugin, going to http://your-WP/index.php?filter[post_type]=post&filter[posts_per_page]=1 should get you a JSON representation of your latest post. Sweet!

¶ Multiplexing requests

As this point we have a very basic API that allows us to pull entries from WordPress based on a set of filters, which may be enough for a very simple project. But what happens when we need to get multiple sets of data to render different elements on a page? It doesn't seem reasonable to send multiple HTTP requests.

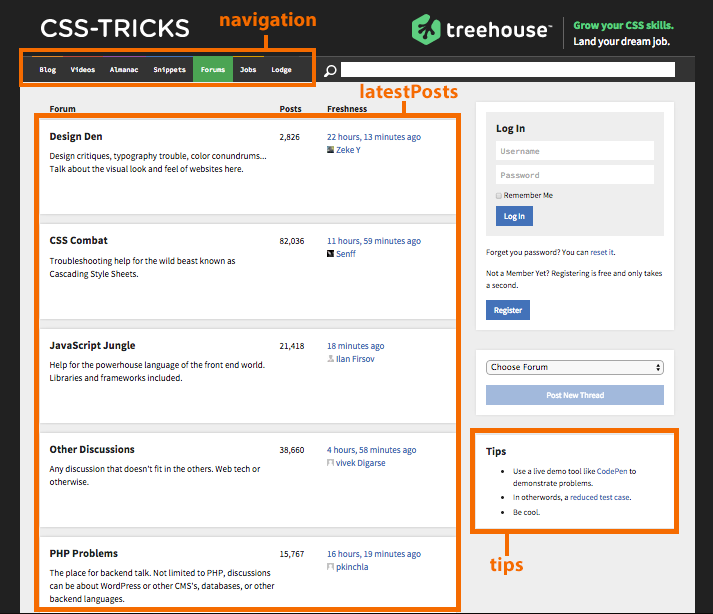

Take the forum page on CSS-Tricks as an example. Beside some meta data that we'd probably need, there are at least three distinct sets of content to pull from the CMS: the items on the navigation bar, the latest posts, and the tips.

We can define our own custom syntax for the API so it accepts the definition of "content buckets" on-the-fly and returns them compartmentalized as a JSON array in the response.

Instead of passing the filters as a simple array in the URL, we can attach a label to each of them to say that they belong to a certain bucket. Going back to the example above, the URL for a multiplexed request could look like this:

?navigation:filter[category]=navigation&latestPosts:filter[type]=post&tips:filter[slug]=tipsWhich would return a JSON structure like this:

{ "navigation": [ { "ID": 1 (...) }, { "ID": 2 (...) } ], "latestPosts": [ (...) ], "tips": [ (...) ]}This gives the API consumers easy access to the different bits of content they require without any additional effort.

The function hijackRequests can be modified to implement this feature.

public function hijackRequests() { $usingBuckets = false; $buckets = array(); $entries = array(); foreach ($_GET as $variable => $value) { if (($separator = strpos($variable, ':')) !== false) { $usingBuckets = true; $bucket = substr($variable, 0, $separator); $filter = substr($variable, $separator + 1); } else { $bucket = 0; $filter = $variable; } $buckets[$bucket][$filter] = $value; } if ($usingBuckets) { foreach ($buckets as $name => $content) { $entries[$name] = get_posts($content['filter']); } } else { $entries = get_posts($buckets[0]['filter']); } $this->writeJsonResponse($entries);}¶ Adding galleries and custom fields

Our JSON representation of posts relies on the information returned by get_posts(), but there are some things missing there that you'll probably want in your feed, such as image galleries and custom fields. We can append that information ourselves to the JSON feed with the help of the functions get_post_galleries_images() and get_post_meta().

for ($i = 0, $numEntries = count($entries); $i < $numEntries; $i++) { $metaFields = get_post_meta($entries[$i]->ID); $galleriesImages = get_post_galleries_images($entries[$i]->ID); $entries[$i]->galleries = $galleriesImages; foreach ($metaFields as $field => $value) { // Discarding private meta fields (that begin with an underscore) if (strpos($field, '_') === 0) { continue; } if (is_array($value) && (count($value) == 1)) { $entries[$i]->$field = $value[0]; } else { $entries[$i]->$field = $value; } }}¶ Final thoughts

The solution described in this article barely scratches the surface of what building an API entails. We haven't touched on things like authentication, request types for write access (POST, PUT, DELETE), multiple endpoints for different types of content (users, categories, settings), API versioning, or JSONP support.

Instead of providing a production-ready product, this solution is meant to show the inner workings of a WordPress API, which will hopefully inspire people to create custom solutions, or extend existing ones, to fulfill their specific needs.

In all truth, creating a bespoke API solution is not for everyone. WP REST API is an established and mature product and will be part of WordPress core soon, so using something like that is probably a wiser choice.

Above all, the purpose of this article is to entertain the idea of taking a widely-used, commercially-proven, and mature product like Wordpress and using it as an API-first content management system. It means stripping out a major part of WordPress and losing the benefits of things like SEO plugins and easy theming, but you gain the freedom of a platform-agnostic system.

What are your thoughts? ∎