I vividly remember my first encounter with a content management system: It was 2002 with a platform called PHP-Nuke. It offered a control panel where site administrators could publish new content that would be immediately available to readers, without the need to create/edit HTML files and upload them via FTP (which at the time was the only reality I knew).

Once I'd made the jump to a CMS, I didn't look back. CMSs quickly became part of my toolkit as a web developer, and I didn’t really stop to question how they worked. I spent a lot of time learning my way around the various components of the web stack; falling in and out of love with different languages, paradigms, frameworks and tools. It took me a long time to stop and think about the most important part of any system: how it manages and stores content.

I set out on a quest to learn more about what's under the hood of a CMS: how it really works and what it actually does when we ask it to handle things like users, articles or taxonomy.

I realised there's something curious about the way platforms like WordPress or Drupal had evolved, in that they became much more than just content editing tools, gradually turning into the backbone of entire systems. These platforms - which power millions of websites - control everything from the database and its structure to the business logic, all the way down to the front-end templates.

This seemed to me to be a lot of power and responsibility for a single tool. I wanted to find out if that could be a problem.

¶ Looking around and ahead

We live in a multi-channel and multi-device world. It's critical that different types of systems - like third-party websites or native applications - are able to interact with your data. Are the current crop of CMS platforms prepared for this?

For example, WordPress runs on PHP with a MySQL database. Does that mean that every other system that needs to communicate with it needs to run PHP? If other systems want to insert new data, do they need to be able to connect to a MySQL database?

In an ideal world, the system would be able to communicate using a language that others could understand, regardless of the technology it’s written in.

And what happens if your content management requirements change? Editorial workflow plays a fundamental role in many organisations, and as they evolve and grow (or shrink!) it’s only natural that their processes will need to change too. Some CMSs can adapt to meet a new set of requirements, but many can’t.

If your CMS can’t adapt to changing requirements you could easily find yourself looking for a new system. This raises many more questions:

- What happens to the existing data structure? Is it flexible enough to be plugged into another platform?

- Are you wed to your existing tech stack?

- How much refactoring will be required to adapt your front-end templates to a new CMS?

It’s also important to consider a more extreme scenario: what if there isn’t a website at all? Downplaying the role of a web presence in favor of a native application is a fairly common occurrence. Indeed many projects might not involve a website at all. Is it still okay for a traditional web CMS to be running the show?

From my perspective I want to give editors a single platform that they can use to publish content, regardless of the end systems that will consume it. Remember that for an editor the CMS is their only window to the world; they spend time working with the editing interface. Changing their interfaces to allow support for different devices over time, or as is more common, forcing them to create and publish content in more than one place to target those devices, has a severe impact on productivity.

¶ Headless CMS and COPE

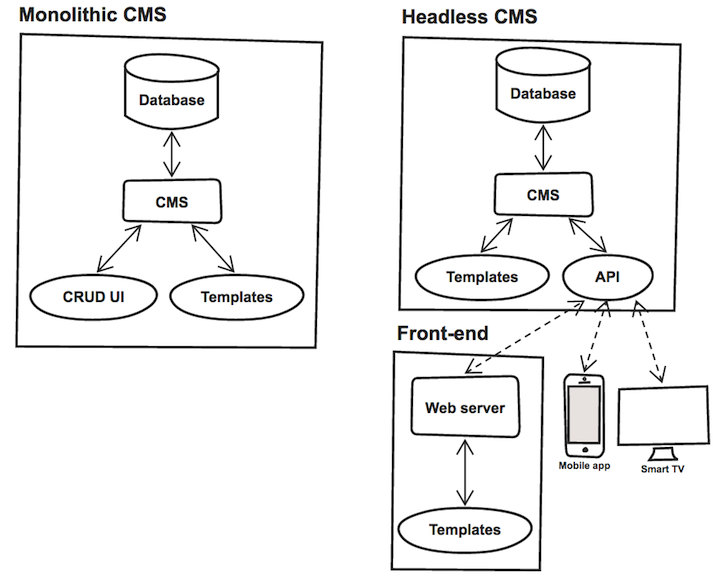

A typical CMS is a monolithic application with at least four components under the hood:

- A data layer where all the content is stored;

- A web-based interface where editors can create and edit content, as well as manage taxonomy and multimedia assets (CRUD UI);

- An interface where site administrators can create and design pages in the form of templates;

- A system that applies content from the database against the templates, generating an output to be consumed by end users (in the case of a website, this will be HTML).

The concept of a headless CMS sets out to tackle this tight coupling of components, removing the concerns highlighted above. The idea is simple: separate numbers 1 and 2 from 3 and 4, adding an API layer that receives and delivers data to the database and communicates with the outside world using a universal language (typically JSON).

Working in this way the front-end is completely decoupled from the data that feeds it, which means it’s no longer limited by the tech stack adopted by the CMS - you could have a Node.js server pulling data from a headless Drupal running PHP, or even a static HTML page getting data from the API using a client-side JavaScript application.

Because pretty much anyone can speak JSON, this also creates the possibility for other systems to consume the data, without forcing editors to publish it multiple times on different platforms. This key principle is the basis of COPE (Create Once, Publish Everywhere) and is a powerful way of delivering content to a multi-medium, multi-device audience.

This was the approach I took when asked by a publishing company to make their WordPress installation capable of delivering content to multiple front-end systems running on different tech stacks (as well as native mobile applications and advertising units).

I created a custom API layer, on top of WP REST API, and documented the journey in an article that you can find here. What you’re now reading is a follow up to that: my continued pursuit of a truly decoupled, flexible and scalable COPE system.

¶ Enter Microservices

The headless CMS approach solved most of my concerns, but not all of them. Even though the data was now detached from the front-end, the database and the CMS were still very much coupled together: still a problem if I wanted to change the CMS because, as the diagram shows, everything that goes in and out of the database still goes through it. (Even the new shiny API that communicates with the outside world.)

This setup also raises questions about scalability: with the CMS and API glued together, how easy is it to scale the system? For example the nature of the traffic hitting those two components will be significantly different, so it would probably make sense to put them under different load balancers.

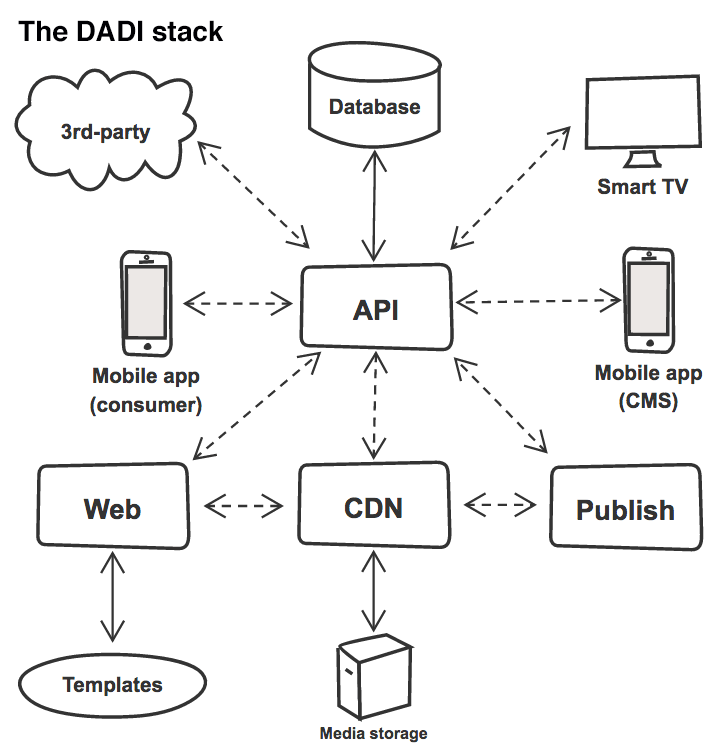

To tackle this I wanted to split the CMS from the API and run them both as self-contained and deployable services. I started working with the guys at DADI, using their open-source platform for content and data management, which is built specifically in support of microservices and the principle of COPE. Their stack is a suite of modular, interchangeable and deployable services, built on Node.js, with the following components:

¶ API

A high-performance RESTful API. Content is stored as documents and grouped in collections. Each collection is defined with a JSON schema file, where fields, validation rules and other data attributes are defined.

Documents are stored and retrieved by querying collections on specific REST endpoints. In addition to this, API also exposes endpoints to edit any configuration file, such as collection schemas, meaning that you can also use REST to create or edit collections.

To provide maximum flexibility it also offers custom endpoints, which can respond to any of the REST verbs with custom logic (and make use of the data models to query the database), as well as hooks that trigger custom routines at key moments in the lifecycle of a request.

To make the integration of API with other systems even easier, there’s a suite of libraries like Passport, to abstract the authentication layer (available for Node.js, PHP and React Native), or API wrapper, a high level toolkit for performing CRUD operations.

¶ Web

A schemaless templating layer that can operate as a standalone platform or with DADI API as a full stack web application. Currently ships with Dust.js as its templating engine (support for more engines is in the works), allowing templates to be rendered both on the server and on the client.

When connected to an DADI API instance, DADI Web can make use of data sources to access collections, with documents made available to the templates automatically. Similarly to hooks in DADI API, it offers maximum flexibility in the form of events, which are modular pieces of functionality that can be attached to a page and executed at render time.

¶ Publish

Full-featured editorial and content management interfaces designed to optimise editorial workflow.

Built with flexibility at its core, it features an advanced layout builder to create article-like documents, with the power to mix and match different elements (like paragraphs, images or media embeds) in a single construct whilst still storing them individually as separate fields.

This makes it easy to generate different versions of an article without having to scrape Markdown or HTML: for example, you can get a version of an article with just the images along with their captions, the pull quotes and the title, or the first three paragraphs.

It ships with collaboration and full revision history baked in.

¶ CDN

A just-in-time asset manipulation and delivery layer designed as a modern content distribution solution.

It has full support for caching, header control, image manipulation, image compression and image format conversion. From a raw image, you could request multiple variations on-the-fly, such as crops with different sizes and resolutions (think responsive images) or even a blurred version.

CDN includes a content-aware cropping tool that is capable of analysing the content of an image to automatically find a good crop for a certain size, which is a game changer for image art direction.

The next version will introduce the concept of routes, a set of rules that allow you to deliver different variations of an asset based on conditions like the user’s device, language, location or connection type.

When compared to existing headless CMS solutions, which are really just monolithic applications adapted to provide an API-first approach as an afterthought, the DADI platform is actually COPE by design, and the separation of concerns using microservices is at its core.

¶ A Real Case

My team has just helped a digital publishing platform startup get their product live. The deliverables included two native mobile applications (Android and iOS), a responsive website, and a CMS, all within a very challenging timeline (think days and weeks, not weeks and months).

Because all of the components of the DADI stack are independent from each other, we could build most of the deliverables in parallel. The first component to be designed was the API layer, as it was responsible for feeding the content to all the user-facing applications, as well as to multiple syndication platforms and a third-party email delivery platform used for all marketing and customer communication.

By directly translating business logic into data structures and validation patterns we established a format for data representation, and with the API ready early in the process, the different teams could work simultaneously on their deliverables without affecting others.

We had one team working on the native mobile applications, another working on the responsive website (using DADI Web), an engineer deploying and customising an installation of DADI Publish and another handling asset manipulation and delivery using DADI CDN.

This separation of concerns liberates people to focus on their own area of expertise. A front-end engineer could complete the web layer having consumed data from API without ever having to see its implementation.

One of the features of the native applications is a basic content management interface, where editors can easily create new articles on the move, meaning that the apps themselves are fulfilling a key role from a traditional CMS. Of course because everything is modular, that is absolutely fine.

The beauty of building with microservices is that it works for projects of any size: a small project where the same instance runs an API, a web layer and editorial interfaces; a large project with dozens of APIs feeding multiple Web fronts controlled by one or more Publish instances; and anything in between. With any possible combination of components, the system can gradually scale from one extreme to the other as the requirements change over time.

This gets even more interesting when cloud computing services such as Amazon AWS are thrown into the mix. If a system has a sudden traffic spike, it can be quickly scaled to tens of instances within a particular layer instead of one, scaling back down to normal when things calm down.

¶ Wrapping Up

We've come a long way since 2002 and PHP-Nuke! Our expectations as users and editors have increased exponentially, and the device landscape has changed beyond all recognition.

It's difficult to predict what the next challenge will be, and of course no system is completely future proof. But I believe that the clean separation of concerns that microservices enable get you as close to that unobtainable goal as possible.

For me the most exciting thing about all of this is that the platform I’ve showed you is available for anyone to use and mess around with. If you’re really game, you can even contribute to the projects.

Feel free to ping me on Twitter if you have any questions or need a hand with setting up DADI. ∎