This article is part of a series called «Microservices and Node.js»:

- Introduction to microservices

- The principles of microservices

- Microservices vs. Service-Oriented Architecture

- Microservices: not a free lunch

- Microservices + Node.js

In the previous article, we introduced the concept of microservices and established a parallel with the traditional monolithic approach. In this article, we’ll continue with that comparison whilst we cover the key principles behind a microservices architecture and how they can help an organisation build better software systems.

¶ Model driven by the business domain

Monolithic systems are typically sliced into the three horizontal layers we saw earlier, and it’s only natural that these boundaries translate into the structure of technical teams. We could have a team of front-end engineers responsible for the presentation layer, a team of back-end engineers in charge of the business logic layer and a team of database architects handling the data access layer. Depending on the complexity of the system and the size of the organisation, it could make sense to slice these even further, decomposing each layer into multiple sub-layers and form more, finer-grained teams around them.

But if you look at the diagram shown in Figure 1-1 of the previous article, you’ll see that there’s nothing about it that is specific to a newspaper organisation. The same diagram could be used to model a school, a restaurant or an airline. The slices have been made based on technological principles, not on the nature of the business domain.

The problem with this approach is that changes to the system are very likely to require modifications to more than one layer — often to all of them. For instance, if we were to add a new field to stories, we would need to change the database schema and update the data access layer, make the business logic layer aware of it and finally update the presentation layer so it displays the new data to users.

This means cross-team coordination and collaboration, which often introduces larger issues. Imagine that Jack’s team of front-end engineers needs some additional data injected into the payload they receive, which should be done in the business logic layer, managed by Sally. Sally’s team is now working on a completely different part of the domain and doesn’t have the resources available to make those changes in time for Jack’s tight deadline, so what will happen? I’ve seen many Jacks cramming the logic into their component, even though it really doesn't belong there, just so that the deadline can be met and everyone can be happy. This violation of the separation of concerns is a recipe for disaster.

The microservices architecture proposes a radically different paradigm for deciding how to divide a system. Instead of slicing around technological boundaries, services are formed from models of the business domain. If we take our newspaper organisation and draw a domain diagram, we’ll identify entities like editor, category, story and comment, among many others. These are very good candidates to become services.

This philosophy also has an effect in the way teams are structured within the organisation. With services focusing on one single part of the domain, a team becomes a group of cross-functional people specialised in that area. It’s easier to achieve leaner, autonomous teams with the power to change and evolve their area of responsibility without depending on others. For example, front-end engineers don’t need to be across the presentation logic for the whole application, only for the particular service they’re looking after. The same applies to any other area of functional expertise.

Adding a new field to a story is now handled entirely by the team responsible for the Stories service, who can make all the necessary changes without depending on anyone else. This approach makes it easier to isolate changes and contain collateral damage, as developers can feel more confident that the code they’re committing won’t introduce unwanted changes to other parts of the system.

¶ Smart endpoints, dumb pipes

In his excellent article about microservices, Martin Fowler uses the term smart endpoints and dumb pipes to describe how microservices should put as little logic as possible on the infrastructure, leaving it up to the services to implement the core logic in their endpoints. He establishes a contrasting parallelism with architectures like the Enterprise Service Bus, or ESB, where the communication channels themselves include logic to transform and even route messages to different endpoints.

With microservices, communication channels should resemble the pipes in Unix applications, where running a command line cat README | grep installation simply takes the output of the first application and passes it onto the second without modifying it in any way. This can be achieved with HTTP request/response or lightweight messaging queues, some of the fundamental building blocks of microservices.

¶ Loose coupling

In a Stack Overflow question asking for a definition of loose coupling, Konrad Rudolph answered with a curious example:

iPods are a good example of tight coupling: once the battery dies you might as well buy a new iPod because the battery is soldered fixed and won't come loose, thus making replacing very expensive. A loosely coupled player would allow effortlessly changing the battery.

The same goes for software development.

Similarly, services should depend as little as possible on the implementation details of other services, making it possible to change or replace a service without that affecting others.

Perhaps a not so obvious example of a tightly coupled system is when more than one service share the same database. Even though the services are completely independent and only communicate with each other via network calls, the fact that they all share the same database schema means that they’re tightly coupled together. If a change to one service requires an update to the schema, all services need to be updated at the risk of breaking.

¶ High cohesion

As defined by Larry Constantine in the late 1960s, cohesion refers to the degree to which the elements of a module belong together. In a component with low cohesion, elements are grouped based on the time at which they’re executed (temporal cohesion) or sometimes with no apparent criteria at all (coincidental cohesion), like a file with utility functions. This makes programs difficult to change, as code associated with one entity can be scattered around multiple parts of the codebase.

Microservices are characterised by a high level of cohesion, with functionality being grouped together because it contributes to a single well-defined task (functional cohesion). As described by Robert C. Martin in his Single Responsibility Principle, “Gather together the things that change for the same reasons. Separate those things that change for different reasons”. This high level of cohesion makes it possible to change all aspects of an entity in a single place, without that affecting other entities in the process.

¶ Independent deployment

In a monolithic application, a small change requires the entire application to be deployed, which is risky, stressful and time consuming. This makes it impractical to deploy every time a new piece of functionality is ready to ship, stopping an organisation from being agile. Instead, this leads to changes building up and being deployed in bulk on a release day, an event that engineers and support teams have learned to absolutely dread, as they know it’s very likely that something will break and everybody will get home late. Creating a culture where developers are fearful of releasing their work is terrible.

With microservices, changes to a service can be deployed independently of the rest of the system. This means that we can get features and fixes to production faster with simpler, quicker and less risky deployments. If something goes wrong, it’s quicker to pin down what failed and it’s easier to fix and redeploy the service, or to simply rollback to the previous working version.

¶ Technology agnostic

When building a monolithic system, you commit to a technology stack at the beginning of the project. This technology will be the only option available for any new piece of functionality that is added to the system at any point in the future, regardless of whether or not it's the best tool for the job. No matter how much and how good the information you have at hand when making that decision is, it's still a massive long-term commitment. Different problems have different optimal solutions, and in an industry with such a fast pace of change, that optimal solution will likely give place to a much better one in the blink of an eye. It’s important that a system allows an organisation to evolve, rather than slow it down.

In a microservices world, there’s nothing stopping different services from using different programming languages, data stores or even operating systems. The newspaper system above could have a Stories service running a .NET application on a Windows server, using a SQL database and Git for version control, and have a Subscribers service built on Node.js, using a MongoDB database on a Unix box and versioned with SVN (yes, really).

This flexibility allows the organisation to always pick the right tool for the job with no pre-established technological constraints. Consequently, it enables teams to more easily experiment with emerging technologies and tools, since the costs of making a bad decision and having to rebuild a service from scratch is much smaller than having to rewrite an entire application.

¶ Resiliency

If a module within a monolithic application misbehaves or fails, the entire system can be affected. With such a tight coupling of components, it’s difficult to contain the damage of a critical error and prevent it from spreading to other parts of the application (a problem known as cascading failure).

In the 12th century, Zhu Yu wrote that the hulls of Chinese vessels were divided into partitions with upright walls to contain water in case of a breach, preventing the ship from sinking. These walls, called bulkheads, are still used today and the concept is very relevant to software engineering.

The boundaries of a service in a microservices architecture are natural bulkheads, preventing one service to cause the failure of another. This principle makes for more resilient and fault tolerant systems. Scalability on a micro level

When scaling a monolithic application, the entire system needs to scale as a whole, even if there is only one small component that requires more resources. This creates a limit to how much the system can scale and makes scaling expensive.

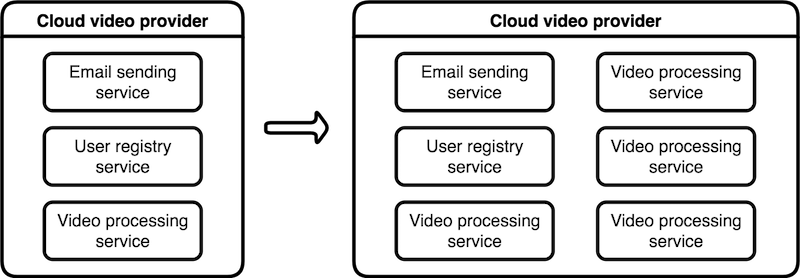

By having components as isolated services, you can scale specific parts of the system individually, as needed. For example, a cloud video provider would probably need to scale its video processing service a lot more and more frequently than its email delivery service, so they could just spin up more instances of that one service, leaving others untouched, as shown in Figure 1-3.

With the rise of elastic cloud computing environments like Amazon AWS, where it’s possible to automatically scale instances on demand, both vertically and horizontally, scalability on a micro level allows each component to dynamically scale up and down depending on its throughput, ensuring healthy performance metrics at all times.

¶ Automation

We’ve seen the benefits of being able to deploy individual services independently of the rest of the system, but that also introduces some challenges. In a monolithic world, there's just a single application that needs to be pushed to a live environment, regardless of how convoluted the deployment process might be. Even if you manually have to provision a machine and pull a Git checkout, it’s still manageable. If you’re looking to have dozens, or even hundreds of microservices to deploy, that won’t cut it.

To work with microservices at scale, you need to invest in an infrastructure that promotes a high level of automation. A prime example of that is a Continuous Delivery pipeline, where each commit to a version-controlled repository is a candidate for a release, with the ability to go through various test suites and be automatically deployed to a myriad of staging environments.

Rigorous tests are a key ingredient to a successful microservices system. When deploying changes to a service, developers need to feel confident that existing live consumers won’t break. A highly automated deployment flow with a comprehensive test suite is the only way to achieve this.

¶ Next in the series

In the next article of the series we’ll look at Service-Oriented Architecture, a software development paradigm from the early 2000s that also promoted decoupling through the creation of technology-agnostic, independent services – specifically, we’ll look at how, if at all, this concept relates to microservices. ∎

Next in the series: Microservices vs. Service-Oriented Architecture