Server-side rendering (SSR) is a relatively new addition to the list of web development buzzwords, and that’s not because rendering websites on a server is a new concept – it’s just that until not too long ago, it didn’t make much sense to render them anywhere else.

The web was originally conceived as a collection of documents. When someone types an address, the browser talks to a server and asks for the content located at that URL, to which the server responds with a document formatted to a specific structure (HTML). The browser can then parse the document, request any additional resources it may link to and finally put the web page on the screen for the user to see and interact with. If they click a link on that page, the entire process is repeated.

But a lot has changed on the web and these days sites behave less like documents and more like full-featured applications, with a level of fluidity and responsiveness that is somewhat incompatible with the flow above. In essence, it’s impossible to build a snappy experience on the web if every change to the interface must wait for a round-trip to the server.

That brings us to the current standard for the modern web, where an increasing number of powerful and complex client-side JavaScript applications take over many of the responsibilities that used to belong to the server. This includes everything from rendering content on the screen, updating it and even fetching the data that feeds it – all of this takes place without the user leaving the page.

¶ Server-side vs. client-side rendering

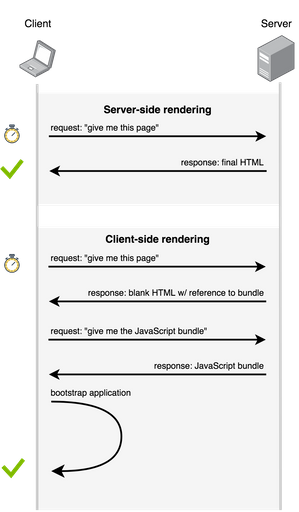

Whilst the difference between server-side and a client-side rendered websites may be subtle to the end user, the underlying architecture and the lifecycle of requests are fundamentally different. In a pure client-rendered application, the server doesn’t need to fetch, format and deliver any content to the browser. So what’s left for it to do? Very little, other than delivering the JavaScript application itself (the bundle file) and an almost blank HTML file that references it.

This is an important distinction to make: immediately after the browser finishes downloading a client-rendered website from the server, it will not have any content or logic to run with. It will show an empty page until it’s able to download and interpret the application bundle, which in its turn will unwrap itself (or bootstrap) and start populating the page with visual elements. This is in stark contrast with the traditional server-rendered flow described above, where the browser receives pages that are ready for consumption.

You can think of server-side rendering as cutting a fully-grown flower and sending it to someone, whereas client-side rendering would be more like sending the seeds and a pot of dirt, delegating to the consumer the onus of growing and watering the flower on their end.

¶ Server-side rendering on client-side applications

I may have given you the impression that pure client-side rendering is an unavoidable consequence of modern web applications, but that isn’t the case. You can build a client-side application that is also rendered on the server, which in fact is the setup that most people refer to when they use the term server-side rendering.

One of the differentiation points between the two paradigms above is what gets sent by the server as the initial payload: a fully formatted and populated HTML file or a blank file followed by a JavaScript bundle. But why not a combination of both?

Server-side rendering a client-side application (also known as isomorphic rendering) means sending the application bundle alongside a populated HTML file instead of a blank one, so that the content is visible immediately after the server’s response is received. The JavaScript bundle will still need to be evaluated and executed just the same, and it will still take full responsibility of subsequently updating the page, but the starting point becomes a full document instead of a clean slate. The server does the first push and then handles control to the client. For simplicity, we’ll refer to this approach as simply server-side rendering going forward.

In our botanical metaphor above, server-side rendering a client-side application would be like sending someone a grown flower as well as the patch of soil it sits on, so it can continue to grow at its destination.

¶ How to choose

There is no silver bullet when it comes to choosing between server-side and client-side rendering. One might think that the question is a no-brainer, as server-side rendering theoretically offers the best from both worlds, but that’s not entirely true. Let’s look at some of the pros and cons of each approach.

¶ Performance

Server-side rendering offers better perceived performance to the end user, as the page will be populated with content immediately after the server responds. With a client-side application, the user would see a blank page for the duration of time it takes for the bundle to be downloaded and executed.

But on the flip side, a server-rendered application requires more resources from the server, as requests need to be prepared individually. This can significantly reduce the request throughout. On a client-side application, the server will simply be delivering pre-packaged files without having to process them, which puts a lot less pressure on the server’s resources.

It’s important to evaluate whether the server infrastructure can cope with the load required at scale. If on one hand server-side rendering reduces the time it takes for the application to be visible after the response, it may also increase the time it takes for the server to respond in the first place (Time to First Byte).

¶ Engineering complexity

Whilst building modern web applications has been made easy by JavaScript frameworks like React or Vue, it’s not always straightforward to incorporate server-side rendering. Every part of the application must be able to adjust to the environment it’s running on, as different instances of the same component can be loaded on the server and the client interchangeably.

A pure client-side application does not have this extra layer of complexity and is therefore easier to build and maintain.

¶ Search engine optimisation (SEO)

This one is a win for server-side rendering. Remember how we said that the user will see nothing but a blank page immediately after the server responds? Well, so will search engines (sort of).

Now, this is not as big of an issue as it was when client-side applications started to appear on the web – to be clear, pure client-side applications do get crawled by search engines. However, there are still some intricacies around client-side applications and SEO that developers must be aware of. For example, Google delays the indexing of client-side applications by one week, which doesn’t happen when server-side rendering is added to the mix.

¶ When to go with server-side rendering

We saw what server-side rendering entails and what some of its caveats are. So what should you take into account when deciding whether or not to use it, and what are the situations where you definitely should?

In cases where your audience is particularly affected by connectivity issues (e.g. a slow network in a developing country), then you should seriously consider server-side rendering. In this context, every byte of data matters, so you should use the first transfer to get some meaningful content in front of people.

If your application bundle is large, then server-side rendering is usually a good idea regardless of the expected network conditions. In normal circumstances, the server should be able to generate and deliver an HTML page quicker than the time it takes for the client to download and parse a huge JavaScript file.

When performance plays a key factor in your engagement and conversion figures (as it often does), adding server-side rendering can shave off some precious time from the average page load time. You may have to beef up your server architecture to pull this off, but it may work out as an investment that is quickly amortized by increased sales.

Finally, the tech stack your website runs on is also an important factor. Whilst it may be challenging to implement server-side rendering on some technology combinations, others lend themselves particularly well to that paradigm. For example, if you run a static site (i.e. JAMstack), then server-side rendering is almost always a perfect fit, giving you significant benefits with virtually no drawbacks.

The main caveats around server-side rendering are concerned with server resources and scaling – the effort required for the server to prepare the data for each request. In a JAMstack setup, this isn’t really a problem, because pages are statically created upfront by the static site generator. At the time of serving requests, the server simply delivers static files with no additional processing required.

The other caveat we mentioned was engineering complexity, but there are quite a few tools in the JAMstack space that can help you setup, with very little effort, a client-side application that is powered by a static site with server-side rendering enabled. Next.js and Gatsby are some great examples of that.

¶ Conclusion

Server-side rendering for web applications is a powerful concept that can help you take your project to the next level. We saw how it works, what it brings to the table as well as some of the things you should look out for when considering it. ∎